This was originally a guest blog post on atlassian.com.

Redefining what is possible

I work at a large software company which is heavily invested in Subversion. In my division alone, we have 3 repositories, each with 100+ projects. I don’t even know how many repositories and projects we have across the company but it is enough that we have an entire team dedicated to managing our source control, CI and build infrastructure.

The general thought on Git has been that while it may have won the “DVCS Wars”, we could never use it because:

Everyone knows Subversion.

All of our shared infrastructure relies on interacting with Subversion.

It would be impossible to migrate all of our repositories to Git.

Git is too hard for a 'Joe SixPack' developer

… unthinkable!

I have been using Git for the past two years and while I must admit that I hated it at first (mostly because I tried to muddle my way through using my knowledge of Subversion), I am now a convert. I see a lot of value in the workflows that it opens up and if I ever have to manually resolve another Subversion tree conflict, someone is going to get hurt. :-) The idea of going back to using Subversion and giving up everything I had come to rely on was unthinkable. So I set off on a crazy journey to bring Git to my company.

NOTE: At my company we simply call our Subversion projects “repositories”, ignoring that they are usually hosted together inside a Subversion repository. Each project, once imported into Git, is a separate repository so going forward, I will refer to them as repositories.

Git-SVN is not Git

My first thought was to use Git-SVN, mostly because Git-TFS had served me well in the past. It had added appeal because no one had to know that I was using Git-SVN. While this does work, it was frustrating on many levels. The main problem being that Git-SVN isn’t really Git.

On a superficial level, the commands are not the same. Instead of git pull, it is git svn rebase, git push is git svn dcommit, etc. Why is it dcommit instead of commit? The world may never know.

If it had just been syntax differences, I would have stuck with it. However, as I tried to use Git-SVN with my normal workflow, I quickly realized that this … is … not … Git. For example, I had to worry about how I would merge master into my feature branch so that the last changeset on the branch had a Git-SVN reference to my target svn branch. Otherwise my next push (sorry, I mean git svn dcommit) intended for that feature branch could accidentally end up on trunk. Why? Because Git-SVN does not track remotes in the same way as Git. Instead Git-SVN relies on metadata injected into the commit messages, where it appends the path of the repository and the svn revision number.

That said, I did use Git-SVN exclusively everyday for 2 months and its merge capabilities saved my bacon more than once. I do not mean to bash it unnecessarily, only to call out the troubles I ran into thinking that I could simply use Git-SVN just like Git.

Eventually other developers at my company noticed that I was using Git and wanted to try it as well which was all part of my evil plan. However they quickly decided it wasn’t worth the effort, as they would have to repeat the same work that I had just done to configure and import each repository into their own local Git-SVN repository: refining what history should be imported, crafting .gitignore and .gitattributes files, making coffee while importing our giant repositories, etc.

Removing the big bang from our migration

Whenever I would search for help with Git-SVN, I saw mentions of something called SubGit. It initially appeared to be yet another git-to-svn importer but once I realized what SubGit really did, that was a turning point in my git crusade.

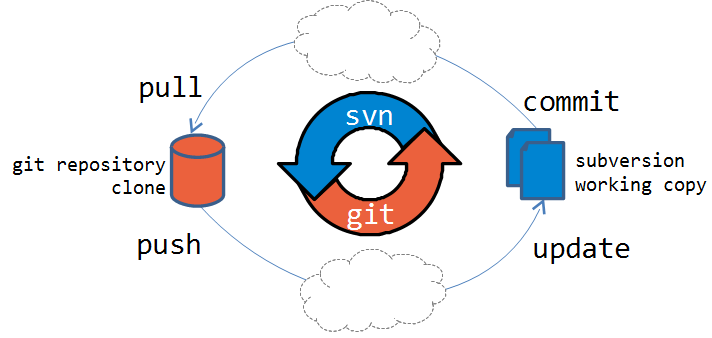

SubGit creates a bidirectional connection between Git and Subversion, safely synchronizing commits between each other. With SubGit I could use “pure Git” and everything I do is synchronized with Subversion. Any intrepid developers using the Git mirror didn’t need to concern themselves with how it was synchronized. Meanwhile everyone else could happily work on Subversion and never even know that I had gone rogue and was using Git. Considering that at this point I had absolutely no buy-in with respect to Git, that aspect was quite critical, buying me time to build up a following of developers and demonstrate how adopting Git was possible… because we already had!

I spent a few days testing out the best way to migrate our Subversion repositories to Git. For example, one repository is a 400MB Subversion checkout (excluding the .svn directory overhead). With over 14 years of history, if I had attempted to import the entire repository into Git, it would have taken weeks and been too large to clone easily. So I settled on only importing history from our last release, which took 14 hours to import and the resulting Git repository is a manageable 600MB. Honestly I have still not figured out what our long term strategy should be with respect to history, other than keeping the original Subversion repositories for any “archaeological digs” that may arise.

Additionally, SubGit can do some interesting things like translating svn-ignore properties to .gitignore files, or creating a .gitattributes file for you. However this significantly increased import time, and long term I wanted to manage these settings independently in Git without them being synchronized back to Subversion properties so I disabled those features.

Eventually I came up with a standard configuration for importing a repository, making the process pretty painless and repeatable. After I had road tested this for a few weeks, I was sure I had finally found a solution to our migration problem. We could stand up these Git mirrors and slowly migrate repositories, teams and infrastructure. The migration could take as long as it needed as neither Subversion nor Git were impacted by the presence of the other. In fact, we plan on migrating our repositories over the course of a year. This really took the pressure off of those in charge of the migration and will allow us to move at a pace that makes sense for our business.

Stash + SubGit go together like peas and carrots

The next step was selecting a Git server, as a bare Git repository only gets you so far and we needed security, web views of changesets, code reviews… basically everything that our current setup of VisualSVN, FishEye and Crucible provided. I was delighted to learn that Atlassian Stash not only had the functionality of FishEye and Crucible baked-in, it also has a plugin for SubGit. The plugin provides a simple UI for bootstrapping a new Git repository from a Subversion repository, handles the initial configuration and ensures that the SubGit synchronization service is always running. Stash has all the features of GitHub (which is what most of our developers were familiar with) plus some extras that in my opinion are must haves in an enterprise environment. There are lots useful plugins such as the Reject Force Push Hook or the Enforce Author Hook which verifies that the Git author on every commit matches the authenticated user.

Another concern was ensuring that people who were not yet using Git didn’t see oddball commits from the Git side. I had a few developers who were working directly off of master and every time they pulled, it was creating merge commits that were being synched back to Subversion. Our policy was to use git pull -- rebase but whenever someone forgot, it would pollute the Subversion repository with empty commits and confusing messages like “Merging master into origin/master…”. In a single weekend, I was able to write a Stash plugin, Reject Merge Commits Hook, a pre-receive hook that identifies “unnecessary” merge commits and rejects the push. The plugin development experience was surprisingly easy, once I learned a bit of Java. Over time it will become more important that we can easily fill any gaps with a plugin and enforce our company policies without too much trouble.

SourceTree teaches old developers new tricks

We kicked off our migration with 10 developers from two teams, a handful of our most active repositories and I thought that the biggest obstacles to the great Git experiment were behind me. I could not have been more off-base! Due to my background with Linux, even though I am a Windows developer by day, I am pretty comfortable in a command line terminal. I didn’t anticipate that my fellow developers would find the switch from TortoiseSVN to Git a confusing awkward mess.

What everyone wanted was big friendly buttons that they could mentally map to what they were familiar with: git pull → svn update, git commit && git push → svn commit, etc. Every Git Windows client that we tried was lacking in a critical area:

- Git for Visual Studio doesn’t support blame and in general feels like they have shoehorned Git into the existing TFS interface

- Git Extensions is ugly and clunky

- TortiseGit is close but doesn’t provide a view of the repository’s overall state

- GitHub for Windows is so limited that it is a total non-starter

What good were all my efforts to migrate us to Git if the developers rejected it as too complicated?

Atlassian SourceTree to the rescue! With few exceptions, a developer can do everything they need in a single UI. Not only that but it provides persistent visual clues as to the state of the repository. You can always see how many commits you are behind/ahead, the current branch, if you are in the middle of a rebase or merge, which files are staged or modified, and it even integrates nicely with our preferred diff tool, Beyond Compare.

Unfortunately, there are still some missing features that will hold up our rollout until they are implemented in the Windows client. Mainly the lack of a tree view of the file hierarchy and interactive rebase support.

Git is the new normal

All of this could not have come at a more opportune time for us. We have just embarked on an enormous effort which involves forking some of our repositories while pulling in the new features that are still being developed on the original repositories into our rapidly diverging fork. This would have been impossible with Subversion, a merge nightmare filled with tree-conflicts and regret. With Git, we are merging two months worth of features without blinking an eye.

Instead of wasting time coordinating “who’s working where” across teams and forks, we are charging forward and people are already taking for granted all of their new found freedom. Previously we would delay any refactoring efforts until our “bug fix” sprint when it was less likely to cause merge problems. Now developers can refactor without fear, when it makes the most sense, during feature development.

Mission Accomplished!

I am still working on changing developer workflows now that we aren’t forced to all work on trunk. Encouraging the use of feature branches, so developers can commit and push regularly, instead of sitting on local changes because the feature isn’t ready to be integrated. I knew we were finally getting the hang of things when one of the developers who had struggled the most with learning Git confided to me that he hated it when he had to work on a repository that wasn’t yet mirrored in Git.

Now here I am, ramping up teams on Git as quickly as I can. Did I mention that this whole Git migration is not my day job? Always a sucker for punishment, I have already switched my sights to pushing for our CI builds to do more: building feature branches, requiring good builds before a pull request can be accepted, automatically merging bug fixes into master, triggering deployments to various environments. Obviously it would be silly to take a moment, sit back and appreciate all that we have accomplished in a few short months. Right?